The Synergistic Potential of Integrated Management for Coexisting Temporomandibular Disorders and Obstructive Sleep Apnea: An Evidence-Based Review

1. Introduction

Temporomandibular Disorders (TMDs) represent a heterogeneous group of musculoskeletal and neuromuscular conditions affecting the temporomandibular joints (TMJs), the masticatory muscles, and surrounding tissue components. These disorders are primarily characterized by pain in the preauricular area, TMJs, or muscles of mastication, often accompanied by limitations or deviations in mandibular range of motion and the presence of TMJ sounds (e.g., clicking, popping, or crepitus) during jaw movement.¹ Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA), conversely, is a prevalent sleep-related breathing disorder marked by recurrent episodes of partial or complete upper airway obstruction during sleep. These episodes typically result in intermittent oxyhemoglobin desaturation, frequent arousals from sleep, and consequent sleep fragmentation.² OSA is associated with significant daytime sequelae, including excessive sleepiness, cognitive impairment, and an increased risk for cardiovascular and metabolic diseases.⁴

There is a growing recognition of the complex interplay between TMD and OSA. The foundational premise of this report is to explore the hypothesis that while targeted treatments for either TMD or OSA in isolation can yield specific, quantifiable benefits, a comprehensive strategy involving screening for both conditions and implementing concurrent management in patients with co-morbid TMD and OSA may result in synergistic improvements in overall health outcomes. Such improvements might manifest as benefits greater than the simple sum of individual treatment effects. This review will critically examine the evidence pertaining to the efficacy of isolated treatments for TMD and OSA, delve into the pathophysiological and clinical links between these two conditions, evaluate the existing data on combined or integrated management approaches, and consider relevant clinical guidelines. The objective is to provide an evidence-based perspective on the potential for enhanced therapeutic outcomes through a holistic approach to patients presenting with these often interconnected disorders. The inherent characteristics of TMD, involving musculoskeletal pain and dysfunction, and OSA, with its associated sleep fragmentation and systemic hypoxia, suggest potential overlapping symptom domains such as fatigue, headaches, and mood disturbances, as well as shared pathophysiological pathways like inflammation and heightened pain sensitivity. This underlying connection implies that the conditions may negatively influence each other, creating a cycle that, if broken by treating both, could offer benefits beyond mere addition. This highlights the importance of a holistic patient assessment over a fragmented, symptom-specific approach in clinical settings.

2. Efficacy of Isolated TMD Treatment: Quantifying Improvement

Temporomandibular disorders encompass a range of conditions with a multifactorial etiology, often necessitating a multidisciplinary therapeutic strategy.¹ Encouragingly, non-surgical interventions are reported to be effective in managing TMD symptoms for over 80% of patients.¹ The therapeutic goal is typically to reduce pain, improve jaw function (such as maximal mouth opening, MMO), and enhance overall quality of life. A variety of non-invasive treatment modalities have been investigated, with reported efficacy varying based on the specific intervention, TMD subtype, patient characteristics, and study methodologies.

3. Efficacy of Isolated OSA Treatment with CPAP: Quantifying Improvement

Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) therapy is widely regarded as the first-line and gold standard treatment for moderate to severe OSA. It functions by delivering pressurized air through a mask, creating a pneumatic splint that maintains upper airway patency during sleep, thereby preventing apneas and hypopneas.⁴ CPAP has been shown to effectively reduce the Apnea-Hypopnea Index (AHI), the primary metric for OSA severity, and improve associated daytime symptoms.³

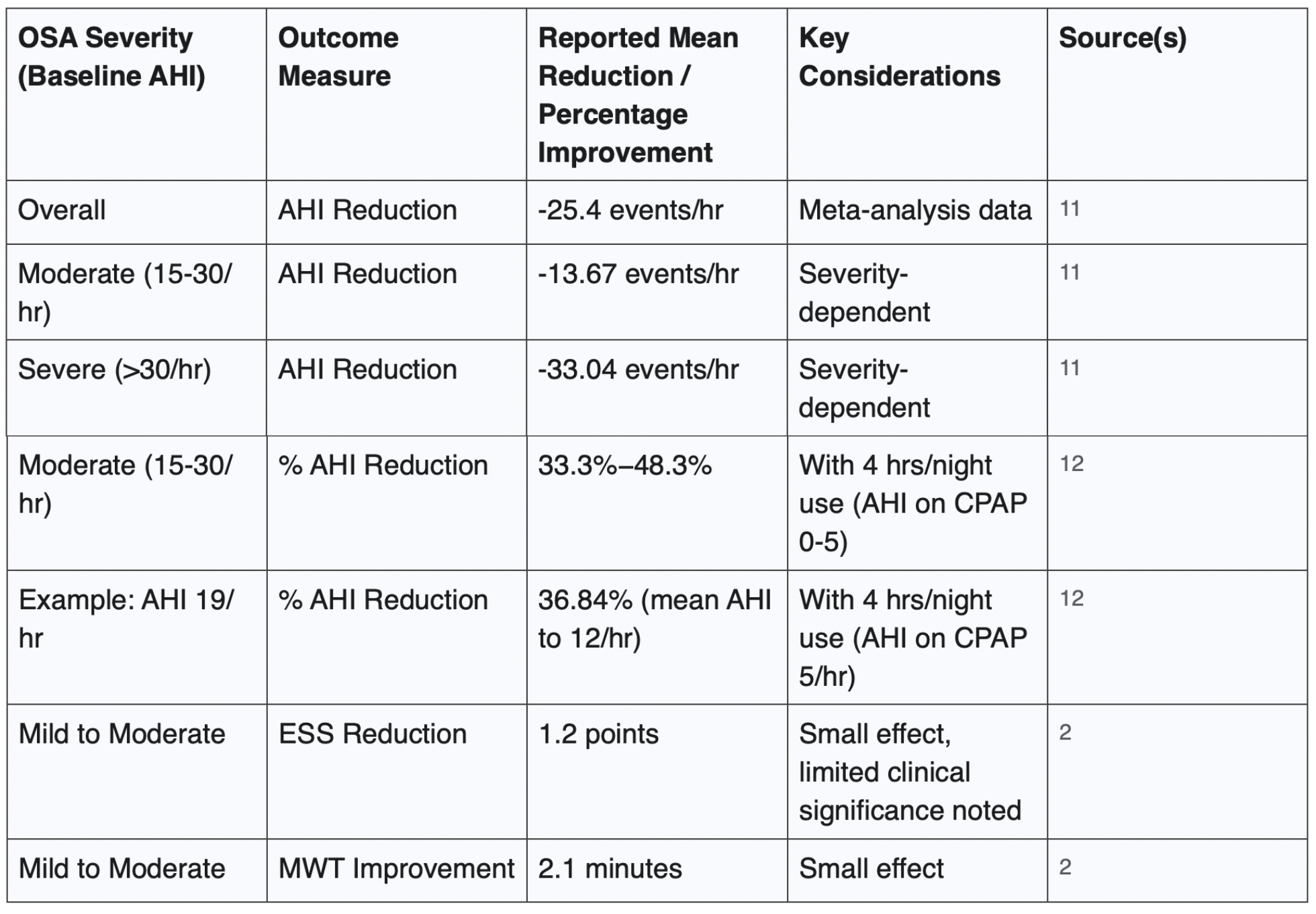

Quantitative data from various studies illustrate the impact of CPAP on OSA parameters:

Overall AHI reduction: Meta-analyses indicate that CPAP can reduce the AHI by a mean of approximately -25.4 events per hour of sleep.¹¹

Severity-dependent AHI reduction: The magnitude of AHI reduction with CPAP is often greater in patients with more severe baseline OSA. For instance, one analysis reported mean AHI reductions of -13.67 events/hour for moderate OSA and -33.04 events/hour for severe OSA.¹¹

Impact of compliance on AHI reduction: CPAP efficacy is heavily dependent on nightly hours of use. Mathematical modelling and clinical observations show varied percentage reductions based on compliance.¹² For example, a patient with a baseline AHI of 19 events/hour, using CPAP for 4 hours per night (with an assumed AHI of 5 events/hour while on CPAP), would experience a reduction in their mean nightly AHI to 12 events/hour, equating to a 36.84% improvement.¹² For patients with moderate OSA (baseline AHI 15-30), 4 hours of nightly CPAP use (achieving an AHI of 0-5 on CPAP) can result in AHI reductions ranging from 33.3% to 48.3%.12 To achieve a target AHI of less than 5 events/hour, CPAP use for 66.67% to 83.33% of the night (i.e., 5.3 to 6.7 hours, assuming an 8-hour sleep period) may be necessary.¹²

Beyond AHI, CPAP therapy has been shown to affect other parameters:

Subjective daytime sleepiness, often measured by the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), can be reduced. One meta-analysis reported a mean ESS reduction of 1.2 points in patients with mild to moderate OSA.²

Objective daytime wakefulness, assessed by the Maintenance of Wakefulness Test (MWT), can improve, with one study showing an increase of 2.1 minutes.² However, it is also noted that for individuals with mild to moderate OSA, the improvements in sleepiness may be small and of limited clinical significance.²

Table 2 presents a summary of CPAP therapy efficacy for OSA.

Table 2: Efficacy of CPAP Therapy for OSA

A critical determinant of CPAP's real-world effectiveness is patient adherence.¹² Despite its efficacy, CPAP therapy is associated with challenges, including mask discomfort, air leaks, nasal congestion, and claustrophobia, which can lead to suboptimal compliance.⁴ Some studies suggest that compliance with CPAP may be lower than with alternative therapies like Mandibular Advancement Devices (MADs).¹³

While CPAP demonstrates substantial AHI reduction, its impact on patient-reported outcomes such as subjective sleepiness or quality of life does not always directly correlate with the degree of AHI improvement, particularly in mild-to-moderate OSA.² For instance, one analysis noted that no significant difference was observed in quality of life outcomes, suggesting the reason for this to be lower CPAP compliance.¹³ This suggests that AHI, while a crucial physiological marker, may not be a sufficient sole measure of overall treatment success from the patient's perspective. Factors like device tolerance, comfort, and the persistence of residual symptoms play a significant role in the patient experience.

The profound dependence of CPAP effectiveness on adherence means that the quoted "improvement" percentages are highly variable in practice and often fall short of what is achievable under ideal, full-night usage conditions. For example, mathematical modelling indicates that even with 4 hours of nightly use (a common threshold for defining compliance), a patient with severe OSA (e.g., baseline AHI of 60) would only see their average AHI drop to approximately 32.5 events/hour.¹² This reality has significant implications: if co-existing TMD (e.g., pain, restricted jaw movement) maintains the mandible in a retruded position, this would indirectly indirectly limit the benefits achievable from CPAP therapy alone. This observation further strengthens the rationale for addressing TMD in OSA patients to potentially improve CPAP tolerance and, consequently, its effectiveness.

4. The Role of Mandibular Advancement Devices (MADs) in OSA and TMD Management

Mandibular Advancement Devices (MADs) are oral appliances designed to treat OSA by protruding and stabilizing the mandible, thereby enlarging the upper airway space and reducing its collapsibility during sleep.¹⁵ They represent an important alternative to CPAP, particularly for patients with mild to moderate OSA, or for those who are intolerant to or refuse CPAP therapy.⁷

MAD Efficacy for OSA:

MADs have demonstrated clinical effectiveness in improving OSA parameters. A meta-analysis reported that MADs significantly reduce AHI, with a mean reduction of -9.3 events/hour.¹¹ Another systematic review focusing on oral appliances (which include MADs) found overall AHI improvements of 48% in mild OSA, 67% in moderate OSA, and 62% in severe OSA.¹⁶ While CPAP generally achieves a greater reduction in AHI compared to MADs (e.g., mean AHI reduction of -25.4/hr with CPAP versus -9.3/hr with MAD in one direct comparison 11; CPAP noted as more efficient in AHI reduction in 13), improvements in subjective daytime sleepiness (ESS) can be comparable between the two therapies.¹¹ Patient preference and long-term compliance may also be better with MADs for some individuals.¹³

Impact of MADs (for OSA) on TMD Symptoms:

The interaction between MAD therapy for OSA and TMD symptoms is complex and has been a subject of considerable research, yielding mixed findings.

Potential for TMD-related side effects: The anterior mandibular positioning induced by MADs can lead to transient side effects, including jaw muscle soreness, TMJ discomfort or pain, tooth tenderness, and possible changes in dental occlusion as suggested by some (and this is where I tend to disagree and suggest that if there are changes, it’s likely because the mandible is retruded to begin with).¹⁴ These symptoms are often reported as mild to moderate and tend to resolve within the first few months to a year of use with appropriate management.¹⁵

No significant exacerbation of pre-existing TMD: Importantly, a meta-regression analysis from a systematic review indicated that patients with pre-existing signs and symptoms of TMD do not experience a significant worsening of these symptoms when using MADs for OSA treatment.¹⁹ This suggests that baseline TMD is not necessarily a contraindication for MAD therapy.

Potential improvement in TMD symptoms: There is also evidence suggesting that MAD therapy for OSA might, in some cases, alleviate certain TMD-related symptoms. The same systematic review 19 noted that OSA treatment (encompassing MADs) can be beneficial in reducing headache intensity. Furthermore, a prospective cohort study cited within this review observed significant improvements in the intensity of pain-related TMD and headache attributed to TMD in patients with OSA after 18 months of initiating OSA treatment.¹⁹

Comparative studies (MAD vs. CPAP regarding TMD effects): A study by Nikolopoulou et al. (2020), as referenced in several sources 15, compared MADs and CPAP over a 6-month period. It found low TMD pain frequency and no significant difference in mandibular function impairment between the MAD and CPAP groups, suggesting that MADs do not inherently pose a greater risk for TMD issues than CPAP in the medium term.

The management of MAD therapy by a qualified dentist is crucial for optimizing efficacy and minimizing adverse effects, including those related to TMD and dental occlusion.¹⁸ Strategies such as gradual titration of mandibular protrusion with specific appliances that are custom-adjusted to develop this titration (BiteAlignTM), and regular follow-up can mitigate potential problems.

The impact of MADs on TMD is evidently not uniform; it appears to be influenced by factors such as the patient's baseline TMD status, the specific design and titration of the MAD, the duration of use, and patient compliance. This variability implies that with careful, individualized management by a dentist experienced in dental sleep medicine, MADs can be a viable and safe OSA treatment option even for patients with TMD concerns. In some instances, MADs may offer collateral benefits for TMD symptoms. This could occur if the OSA itself is a contributing factor to the TMD symptomatology (e.g., through OSA-related bruxism, or sleep fragmentation leading to muscle pain and hyperalgesia). In such scenarios, effective OSA treatment with a MAD, despite its mechanical action on the mandible, could lead to an overall net improvement in TMD symptoms by addressing an underlying etiological driver.

Considering the user's specific interest in "MAD and CPAP" for exponential improvement: if a patient presents with severe OSA (where CPAP is typically the primary recommendation) and co-existing TMD, a MAD might not be the first choice for OSA treatment. However, a MAD could be employed as a TMD-specific therapeutic appliance used concurrently with CPAP for OSA. Alternatively, if a patient with mild to moderate OSA and TMD uses a MAD for OSA, and this therapy coincidentally alleviates their TMD symptoms, this represents a form of combined benefit. The simultaneous use of both MAD and CPAP for OSA itself is less common but is a recognized combination therapy for very severe or complex OSA cases, though this specific scenario is not the primary focus of the available data regarding TMD interactions.

5. The Interplay Between TMD and OSA: Rationale for Integrated Screening and Management

A substantial body of evidence points to a significant association between TMD and OSA, suggesting shared underlying mechanisms and reciprocal influences that provide a strong rationale for integrated clinical approaches.

Prevalence of Comorbidity:

Studies consistently report a higher prevalence of OSA among patients with TMD, and conversely, an increased occurrence of TMD signs and symptoms in individuals with OSA.

Systematic reviews indicate that cross-sectional studies demonstrate a higher OSA prevalence in TMD cohorts.²¹

Estimates suggest that over 28% of TMD patients may have concurrent OSA, while up to 51% of OSA patients may exhibit signs and symptoms of TMD when compared to control populations.²¹

Longitudinal data further strengthen this link: OSA symptoms have been associated with a 1.73-fold increased hazard for the first onset of TMD and a 3.63-fold increased odds for chronic TMD.²²

The co-occurrence of conditions like bruxism (both sleep and awake), sleep apnea, and migraine is notably high in TMD patient populations, with OSA being more frequent in TMD patients than in the general population.²³

Shared Pathophysiological Mechanisms and Risk Factors:

The connection between TMD and OSA is more than mere coincidence; several plausible biological pathways may link these conditions:

OSA-induced Hyperalgesia: Sleep fragmentation and intermittent nocturnal hypoxemia, hallmarks of OSA, are strongly implicated in the development of hyperalgesia (an increased sensitivity to pain). This heightened pain perception can exacerbate existing TMD pain or lower the threshold for developing new TMD symptoms.²¹

Inflammatory Pathways: Chronic intermittent hypoxia in OSA can trigger systemic and local inflammatory responses. Increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), have been observed in OSA patients. These cytokines can modulate pain signaling pathways, potentially contributing to the pain experienced in TMD.²¹

Sleep Disturbances and Arousal: Patients with TMD, particularly myofascial TMD, often exhibit higher levels of sleep disturbances, respiratory events, and arousals during sleep studies, even if not meeting full criteria for OSA.²¹ These disturbances can contribute to muscle fatigue and pain.

Biomechanical Factors: Conditions like retrognathia (a recessed lower jaw) can be a risk factor for both OSA (by narrowing the pharyngeal airway) and certain types of TMD (by altering TMJ mechanics), and positioning the condyle posteriorly.

Psychosocial Factors: The biopsychosocial model of pain is highly relevant here. Both TMD and OSA are associated with an increased prevalence of mental health disorders such as depression and anxiety.⁶ Chronic pain from TMD can worsen mood and sleep, while poor sleep and daytime fatigue from OSA can exacerbate pain perception and psychological distress, creating a vicious cycle.

Clinical Implications:

The strong association and shared mechanisms between TMD and OSA have significant clinical implications:

There is a clear need for clinicians treating patients with painful TMD to have a thorough understanding of sleep disorders, including OSA, and to consider their prompt diagnosis and management as part of a comprehensive TMD treatment plan.²¹

OSA should be recognized as a potential risk factor for the perpetuation of TMD.²¹

Routine screening for OSA in patients presenting with TMD, and vice-versa, is clinically prudent. Current clinical guidelines are beginning to reflect this: AASM guidelines for OSA recommend incorporating questions about OSA symptoms into routine health evaluations.⁹ Similarly, TMD management guidelines advise identifying co-morbidities and suggest referral for OSA assessment if clinical suspicion arises.⁵

The relationship between TMD and OSA is likely bidirectional and cyclical. OSA can lead to hyperalgesia and inflammation, thereby worsening TMD pain and dysfunction. Conversely, TMD pain, particularly if severe, can disrupt sleep architecture, potentially affect airway muscle tone, or influence sleep position in ways that might exacerbate OSA or the patient's perception of its severity. The psychological distress common to both conditions can further fuel this negative cycle; for example, OSA-induced fatigue and mood alterations could lower an individual's pain tolerance thresholds relevant to TMD. This cyclical interaction strongly suggests that treating only one condition while the other remains active and unaddressed may significantly limit overall therapeutic success and patient-reported outcomes.

The documented shared pathophysiological mechanisms; such as systemic inflammation, centrally mediated hyperalgesia, and the profound impact of sleep disruption on pain modulation and muscle physiology, provide a compelling biological basis for anticipating synergistic benefits when both conditions are effectively and concurrently treated. If OSA contributes to systemic inflammation and hyperalgesia that manifests as or exacerbates TMD pain, then effective OSA treatment should logically reduce these drivers, thereby alleviating a significant component of the TMD symptomatology. Similarly, if TMD pain itself fragments sleep (either independently or by worsening tolerance to OSA therapies), then successful TMD management should improve sleep quality, which can, in turn, improve OSA outcomes or general well-being. Addressing both conditions simultaneously offers the potential to interrupt these negative feedback loops from multiple points, leading to a degree of improvement that might be substantially greater than if only one pathway or condition was targeted. This understanding shifts the clinical focus from merely acknowledging comorbidity to actively seeking strategies for integrated care.

6. Evaluating Outcomes of Comprehensive Management for Co-morbid TMD and OSA: The Quest for "Exponential Improvement"

The central hypothesis under consideration posits that a comprehensive management strategy for patients with coexisting TMD and OSA could yield "exponential improvements," particularly when considering treatments like MADs and CPAP. Evaluating this claim requires careful examination of available evidence for synergistic effects.

Direct evidence from the reviewed materials specifically quantifying an "exponential" (i.e., a statistically interactive and multiplicative) improvement stemming from a defined "MAD and CPAP" combination therapy—where both are used simultaneously for OSA in a co-morbid patient, or one for OSA and the other for TMD—is not explicitly detailed. MADs and CPAP are more commonly discussed as alternative primary treatments for OSA, or in scenarios where a MAD might be used for TMD management alongside CPAP for OSA.

However, there is pertinent evidence suggesting that treating OSA can positively impact concurrent TMD symptoms, which points towards a synergistic benefit:

A prospective cohort study reported in a systematic review 19 is particularly noteworthy. In this study, patients with OSA who received treatment (which could include various modalities such as CPAP or MADs used individually for OSA) demonstrated significant reductions in the intensity of pain-related TMD and headache attributed to TMD after an 18-month follow-up period. Crucially, patients with OSA who did not receive or discontinued OSA treatment showed no significant change in their TMD symptoms over the same period. This finding strongly implies that effective OSA management contributes to the alleviation of TMD, a benefit that would not be achieved by addressing TMD in isolation if OSA remained untreated.

The same systematic review's meta-regression analysis also found that MADs used for OSA do not significantly exacerbate pre-existing TMD symptoms and may be beneficial for associated headaches.¹⁹

When interpreting the phrase "treating those with both MAD and CPAP," several clinical scenarios could be envisaged:

CPAP for OSA and a MAD (or other oral appliance) for TMD: This is a clinically plausible scenario where each therapy targets a distinct condition. The overall benefit would arise from addressing both pathologies.

MAD for mild-moderate OSA (which might also positively influence TMD) with CPAP added or used subsequently: This could occur if MAD monotherapy is insufficient for OSA control, or if a patient has severe OSA where CPAP is primary but a MAD is used adjunctively or for specific TMD relief.

Comprehensive, integrated management: This is perhaps the most relevant interpretation for achieving synergistic effects. It implies that OSA is treated effectively (e.g., with CPAP or a MAD, depending on severity and patient factors) and TMD is concurrently managed through its own appropriate modalities (e.g., physical therapy, specific TMD oral splints which could be MAD-like or different, counselling, pharmacotherapy). The "exponential" or synergistic effect would then arise from the combined positive impact of resolving both distinct but interacting pathologies.

While direct quantification of "exponential" improvement is elusive, the inferred mechanisms for synergy are compelling:

Improved Sleep Quality: Effective OSA treatment (via CPAP or MAD) restores normal sleep architecture and alleviates intermittent hypoxia. This can lead to a reduction in systemic inflammation, a decrease in general pain sensitivity (hyperalgesia), and improved muscle repair processes, all of which are beneficial for TMD.

Enhanced OSA Therapy Tolerance: Alleviating TMD pain and improving jaw function can, in turn, improve a patient's ability to tolerate and comply with OSA therapies. For example, reduced jaw pain might make wearing a CPAP mask more comfortable, or allow for more effective use of a MAD.

Reduction of OSA-Related Bruxism: If OSA is contributing to sleep bruxism (tooth grinding or clenching), effective OSA treatment may reduce these parafunctional activities, thereby decreasing masticatory muscle strain and TMJ loading that can exacerbate TMD.

Improved Psychosocial Well-being: Both TMD and OSA can negatively impact mood and quality of life. Effective treatment of either condition can lead to improvements in psychological well-being, which can have a positive reciprocal effect on the management and perception of the other condition.

It is important to acknowledge the existing gaps in the literature. No studies presented in the reviewed materials offer a direct, quantitative comparison demonstrating that a specific "MAD and CPAP" combination therapy results in an improvement that is mathematically "exponential" (i.e., significantly greater than the sum of the benefits from treating each condition alone). The available evidence points more towards clinically significant additive benefits, with a strong suggestion of modest synergistic interactions when both conditions are appropriately managed, rather than a strictly multiplicative effect.

While some suggest that treating OSA can improve TMD outcomes, it's important to recognize that in many cases, it is TMD, specifically a retruded mandible, that contributes to the development or worsening of OSA, not the other way around. The relationship is often misinterpreted as unidirectional. The term "exponential improvement" could be seen as a colloquial reference to the significant synergistic benefits observed when both conditions are addressed. However, to establish a true synergistic or multiplicative effect, future studies would need to compare outcomes from (a) OSA treatment alone, (b) TMD treatment alone, and (c) combined therapy, particularly in patients with mandibular retrusion, to allow for statistical interaction analysis. Current data, however, are not designed to isolate or quantify this causal direction clearly.

The combined use of mandibular advancement devices (MADs) and continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy, when interpreted as simultaneous treatment for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), is not typically considered a primary management strategy for most patients. However, in cases where CPAP is employed to address OSA and a MAD (or a similar intraoral appliance) is used concurrently to manage temporomandibular disorder (TMD), the hypothesis of a synergistic therapeutic effect warrants consideration.

Emerging evidence suggests that TMD, particularly in the presence of mandibular retrusion, may play a contributory role in the onset or exacerbation of OSA. In such scenarios, the potential for clinical improvement may stem not only from the independent effects of each intervention but also from their interactive impact on two biomechanically and neurologically interconnected conditions.

This distinction holds significant implications for both clinical decision-making and research methodology. Future studies should be specifically designed to assess outcomes in patients with co-morbid TMD and OSA, with an emphasis on multidimensional metrics encompassing structural, physiological, and psychosocial parameters. Such data are essential to determine whether combined treatment offers true synergistic benefits, as opposed to merely additive effects observed when each condition is managed in isolation.

7. Clinical Guidelines and Expert Recommendations for Integrated Care

Current clinical guidelines from various professional bodies are beginning to acknowledge the importance of recognizing and addressing the comorbidity between TMD and OSA, although detailed, fully integrated treatment algorithms are still evolving.

Screening Recommendations:

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) guidelines for the evaluation and management of OSA in adults recommend that questions regarding OSA symptoms (e.g., snoring, daytime sleepiness) be incorporated into routine health evaluations.⁹ A suspicion of OSA should trigger a comprehensive sleep evaluation, which includes a sleep-oriented history and physical examination (looking for risk factors like obesity, retrognathia, increased neck circumference, and high Mallampati scores).⁹ While these general OSA guidelines do not explicitly list TMD as a primary screening trigger for OSA, the presence of shared anatomical risk factors (like retrognathia) or symptoms that could be exacerbated by OSA (like headache or fatigue) may indirectly lead to OSA investigation.

Conversely, guidelines for the management of TMD, such as those from the Faculty of Dental Surgery (FDS) of the Royal College of Surgeons of England, explicitly recommend identifying comorbidities during the patient assessment.⁵ These guidelines state that if there are positive findings suggestive of OSA, an urgent written referral to the patient's general practitioner (GP) is required for further assessment, diagnosis, and management of OSA. Simultaneously, the primary care clinician (often a dentist) should provide the TMD diagnosis, initiate supported self-management for TMD, and arrange for appropriate review.⁵

Expert opinion further supports bidirectional screening. For instance, it has been suggested that patients undergoing TMD evaluation should be routinely asked about sleep quality and symptoms suggestive of sleep-disordered breathing, and conversely, patients diagnosed with OSA, particularly prior to initiating treatments like MADs, should be screened for pre-existing TMDs.¹⁹

Multidisciplinary Management:

There is a consensus that OSA should be approached as a chronic disease requiring long-term, multidisciplinary management involving various healthcare professionals.⁹

For comorbid TMD and OSA, effective management often necessitates close collaboration between orofacial pain specialists, dental sleep medicine practitioners, sleep physicians, and potentially physical therapists or psychologists.¹⁹

The AASM clinical practice guideline on oral appliance therapy for OSA emphasizes the integral role of a "qualified dentist" working in conjunction with a sleep physician for the provision and oversight of MAD therapy.²⁰ This includes initial patient assessment, appliance selection and fitting, titration to efficacy, and long-term surveillance for dental-related side effects or occlusal changes.²⁰

Treatment Algorithm Considerations:

While no explicit, universally adopted combined treatment algorithm for comorbid TMD and OSA is detailed in the provided materials, an inferred approach based on current guidelines and expert recommendations would likely involve the following steps:

A patient presents with symptoms suggestive of either TMD or OSA.

Systematic screening for the comorbid condition is performed using validated questionnaires and clinical examination.

If both conditions are suspected or confirmed:

Comprehensive diagnostic workup is undertaken to confirm diagnoses and determine the severity of each condition (e.g., polysomnography for OSA, standardized diagnostic criteria like DC/TMD for TMD).

A coordinated, multidisciplinary treatment plan is developed. For OSA, this might involve CPAP for moderate to severe cases, or if CPAP is not tolerated or for mild OSA, a MAD could be considered (with careful assessment and monitoring of TMD status). For TMD, management typically starts with conservative, reversible therapies such as patient education, self-care strategies, physical therapy, occlusal splints (which may include specific types of MAD-like appliances or other designs), and pharmacotherapy if indicated.

The impact of OSA treatment on TMD symptoms, and vice-versa, should be monitored. For example, initiation of MAD therapy for OSA requires careful observation for any adverse effects on the TMJ or masticatory muscles.

Regular follow-up appointments with the relevant specialists are scheduled to assess treatment efficacy, adherence, side effects, and to make necessary adjustments to the treatment plan.

Current clinical guidelines advocate for screening and highlight the need for multidisciplinary involvement. However, they generally lack specific, detailed integrated treatment algorithms for comorbid TMD-OSA that are explicitly designed to achieve and measure synergistic outcomes. The AASM guidelines, for example, provide comprehensive recommendations for OSA diagnosis and various treatment options, including collaboration with dentists for oral appliance therapy 9, but do not extensively detail protocols for the co-management of TMD. TMD guidelines, on the other hand, recommend referral for OSA assessment if suspected 5, implying parallel management pathways rather than deeply integrated ones being laid out in extensive detail. The call for closer collaboration between specialists¹⁹ suggests that this is an area with significant potential for development.

The AASM’s emphasis on the involvement of “qualified dentists” in the provision of oral appliance therapy for OSA¹⁰ underscores the reality that these devices directly engage with the complex stomatognathic system, including the temporomandibular joints and occlusion. This makes dental expertise essential in any OSA management strategy involving oral appliances, especially in patients with co-existing TMD. In such cases, the dentist’s role is not only to select and deliver the appliance, but to ensure it is properly designed and adjusted to avoid worsening TMD symptoms, or ideally, to support improvement in both conditions. This reinforces the growing need for structured clinical training in appliance-based care, particularly systems like BiteAlign™, which provide a standardized approach to design and adjustment rooted in neuromuscular and joint physiology. As interest in managing co-morbid TMD and OSA grows, future research must focus on evidence-based, integrated treatment pathways that include criteria for appliance selection, optimal sequencing of care, and clear metrics for evaluating outcomes, especially where synergistic benefits may be possible.

8. Conclusion and Future Directions

This review has synthesized evidence regarding the treatment of Temporomandibular Disorders (TMD) and Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA), both in isolation and with consideration for their common comorbidity.

The findings indicate that:

Isolated TMD treatments, particularly multimodal or combination therapies, can yield significant improvements in pain and jaw function, with reported efficacy varying by modality but often being substantial.¹

CPAP therapy for OSA effectively reduces the Apnea-Hypopnea Index (AHI) and can improve some daytime symptoms, although the impact on subjective sleepiness in mild-to-moderate OSA may be modest, and overall effectiveness is critically dependent on patient adherence.²

Mandibular Advancement Devices (MADs) represent a viable treatment alternative for OSA, especially in patients with mild-to-moderate disease or those intolerant of CPAP. While MADs can induce transient TMD-like side effects, they do not appear to significantly exacerbate pre-existing TMD with proper management and may, in some instances, contribute to the alleviation of certain TMD symptoms, such as associated headaches.¹¹

Revisiting the central hypothesis concerning "exponential improvement" from combined management:

There is robust evidence confirming a significant comorbidity between TMD and OSA, underpinned by plausible shared pathophysiological links, including inflammation, hyperalgesia, and the impact of sleep disruption.²¹

Crucially, evidence, most notably from a prospective cohort study 19, suggests that effective treatment of OSA can lead to concomitant improvements in co-existing TMD symptoms. This supports the concept of a synergistic interaction, where managing one condition positively influences the other, leading to an overall benefit greater than if only TMD were addressed while OSA remained untreated.

Future Directions:

The current body of evidence strongly supports a paradigm shift towards routine bidirectional screening for TMD and OSA and the implementation of more integrated management strategies. Even if the precise "exponential" nature of the benefit requires further quantification, the clinical imperative to address both conditions in comorbid patients is clear due to their high prevalence, shared pathophysiology, and the initial evidence of synergistic benefits. The definition and measurement of "improvement" in this comorbid population also needs to be comprehensive, moving beyond AHI for OSA and VAS for TMD pain to include a broader range of outcomes. Future research should employ a battery of measures, including polysomnography, validated pain and functional assessments (e.g., MMO), quality of life inventories (e.g., SF-36, FOSQ), and psychological screening tools, to capture the full spectrum of benefits from integrated treatment.

To further elucidate the potential for enhanced outcomes and to refine clinical practice, several areas warrant future research:

Prospective, Controlled Trials: Well-designed studies are needed to directly compare the outcomes of: (a) TMD treatment alone, (b) OSA treatment alone, and (c) combined or integrated TMD and OSA treatment in well-characterized comorbid patient populations. These studies should utilize standardized, comprehensive outcome measures spanning physiological, functional, patient-reported (pain, quality of life), and psychological domains.

Mechanistic Studies: Research aimed at elucidating the precise neurobiological, inflammatory, and biomechanical mechanisms underlying the observed synergistic benefits when both TMD and OSA are treated.

Optimizing MAD Therapy in Comorbid Patients: Further investigation into optimal patient selection criteria, MAD designs, and titration protocols for patients with coexisting TMD and OSA is needed to maximize OSA efficacy while minimizing any potential adverse effects on the stomatognathic system, or ideally, enhancing TMD symptom relief.

Development of Integrated Care Pathways: There is a need for the development and validation of practical, evidence-based integrated care pathways and clinical decision-support tools to facilitate routine screening, diagnosis, and coordinated multidisciplinary management of comorbid TMD and OSA.

Clarification of Specific Combined Modalities: If the "MAD and CPAP" combination refers to a novel simultaneous or sequential application beyond current standard practice (e.g., MAD for TMD alongside CPAP for OSA, or specific combined OSA therapies), dedicated studies are required to define its rationale, feasibility, and efficacy in comorbid populations.

In conclusion, while the term "exponential improvement" may be an ambitious descriptor, the principle of achieving significantly enhanced outcomes through the integrated management of coexisting TMD and OSA is supported by current evidence of their interplay and the positive impact of OSA treatment on TMD symptoms. Continued research is essential to translate this understanding into refined, evidence-based clinical protocols that can optimize care for this complex patient population. Successfully demonstrating and understanding these synergistic benefits could ultimately lead to more effective and potentially more cost-efficient healthcare by addressing the substantial burden imposed by these prevalent and interconnected chronic conditions.

Works cited

Comparative Efficacy of Non-Invasive Therapies in ..., accessed May 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11032691/

Continuous positive airway pressure reduces daytime sleepiness in ..., accessed May 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2111183/

Comparative efficacy of sleep positional therapy, oral appliance therapy, and CPAP in obstructive sleep apnea: a meta-analysis o - Frontiers, accessed May 11, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/medicine/articles/10.3389/fmed.2025.1517274/pdf

Long-term health outcomes for patients with obstructive sleep apnea: placing the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality report in context—a multisociety commentary - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed May 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10758567/

www.rcseng.ac.uk, accessed May 11, 2025, https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/-/media/FDS/TMD-Clinician-summary-document-March-2024.pdf

Psychological Outcomes on Anxiety and Depression after Interventions for Temporomandibular Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis, accessed May 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9955945/

Comparison of effects of OSA treatment by MAD and by CPAP on cardiac autonomic function during daytime - PubMed Central, accessed May 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4850173/

Comparative efficacy of sleep positional therapy, oral ... - Frontiers, accessed May 11, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/medicine/articles/10.3389/fmed.2025.1517274/full

aasm.org, accessed May 11, 2025, https://aasm.org/resources/clinicalguidelines/osa_adults.pdf

Clinical Guideline for the Evaluation, Management and Long-term Care of Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Adults, accessed May 11, 2025, https://jcsm.aasm.org/doi/10.5664/jcsm.27497

Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials of oral mandibular ..., accessed May 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5378304/

Reliable Calculation of the Efficacy of Non-Surgical and Surgical ..., accessed May 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3001787/

Effects of CPAP and mandibular advancement device treatment in obstructive sleep apnea patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis - PubMed, accessed May 11, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29129030/

Mandibular Advancement Devices in OSA Patients: Impact on Occlusal Dynamics and Tooth Alignment Modifications—A Pilot Prospective and Retrospective Study, accessed May 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11592911/

The impact of oral appliance therapy and mandibular advancement ..., accessed May 11, 2025, https://joma.amegroups.org/article/view/6727/html

(PDF) Efficacy of Oral Appliance for Mild, Moderate, and Severe Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Meta-analysis - ResearchGate, accessed May 11, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/378267018_Efficacy_of_Oral_Appliance_for_Mild_Moderate_and_Severe_Obstructive_Sleep_Apnea_A_Meta-analysis

The impact of oral appliance therapy and mandibular advancement devices on jaw function symptoms in sleep apnea - AME Publishing Company, accessed May 11, 2025, https://cdn.amegroups.cn/journals/jss/files/journals/25/articles/6727/public/6727-PB1-3236-R1.pdf?filename=JOMA-24-16-final.pdf&t=1733983194

Basic Clinical Management of Temporomandibular Disorders (TMDs), accessed May 11, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/386242783_Basic_Clinical_Management_of_Temporomandibular_Disorders_TMDs

Effects of mandibular advancement device for obstructive sleep ..., accessed May 11, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/335873884_Effects_of_mandibular_advancement_device_for_obstructive_sleep_apnea_on_temporomandibular_disorders_A_systematic_review_and_meta-analysis

Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Snoring with Oral Appliance Therapy: An Update for 2015 - PubMed Central, accessed May 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4481062/

Associations between obstructive sleep apnea and painful ..., accessed May 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9639245/

Sleep Apnea Symptoms and Risk of Temporomandibular Disorder: OPPERA Cohort - PMC, accessed May 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3706181/

Exploring the associations of sleep bruxism and obstructive sleep apnea with migraine among patients with temporomandibular disorder: A polysomnographic study - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed May 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11794979/

Temporomandibular disorders and mental health: shared etiologies and treatment approaches - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed May 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11899861/